Too Much of Too Little & Too Little of Too Much: Part I

How playing into the extremes of Maximalism and Minimalism leaves design lacking: A Journey Through Cultural Extremes Toward the Sophisticated Balance of Arab Aesthetic Philosophy The Crisis of Contemporary Design We have an affinity for aligning ourselves strongly with our likes and dislikes; our cultural discourse more often than not tends to be hyperpolarized. This […]

How playing into the extremes of Maximalism and Minimalism leaves design lacking:

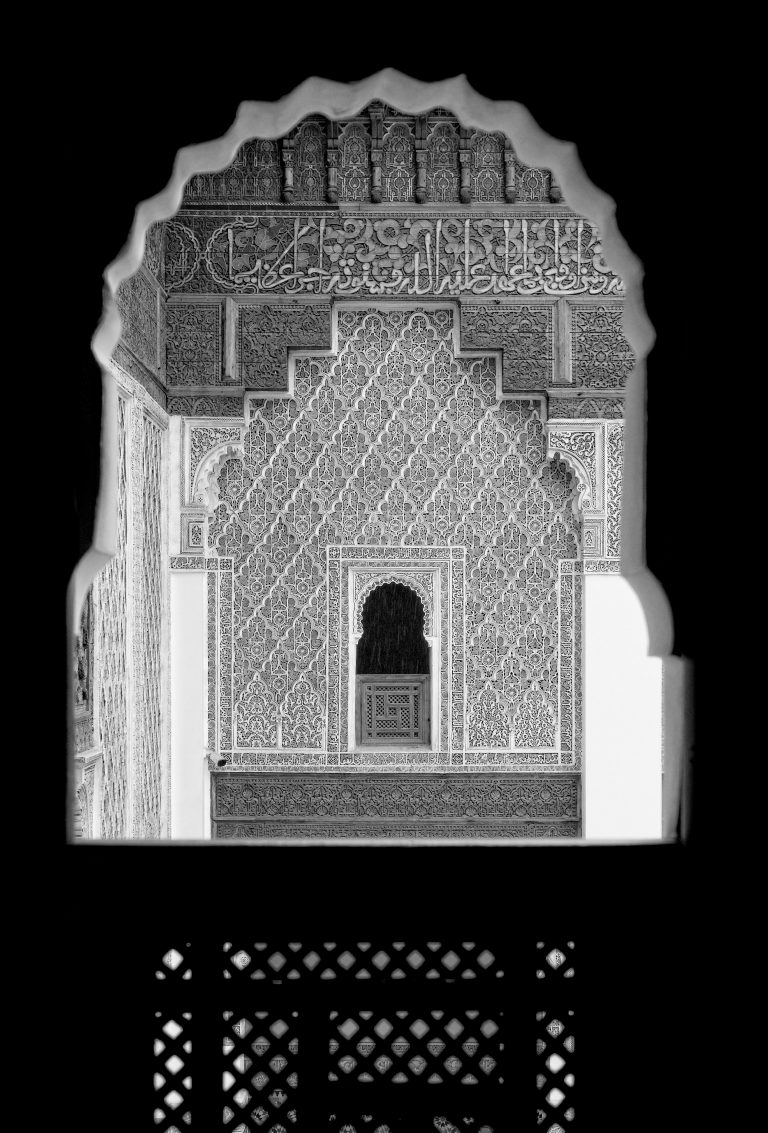

A Journey Through Cultural Extremes Toward the Sophisticated Balance of Arab Aesthetic Philosophy

The Crisis of Contemporary Design

We have an affinity for aligning ourselves strongly with our likes and dislikes; our cultural discourse more often than not tends to be hyperpolarized. This is reflected in how we are failing to achieve balance, or the semblance of it. Design for the past two decades has been plagued by the mundane, dull, and boring. All in the name of the principle “less is more,” which was coined by the Architect Ludwig Mies van der Rohe.

However, what we’ve witnessed is not the thoughtful application of van der Rohe’s principle, but its weaponization against cultures that have historically celebrated visual abundance as a mark of intellectual and spiritual sophistication. This crisis extends beyond mere aesthetic preference—it represents a fundamental misunderstanding of how human cognition processes beauty and meaning.

Recent neuroscientific research reveals that our brains are specifically wired to appreciate complexity, pattern, and cultural significance in ways that pure minimalism cannot satisfy. Contemporary research in neuroaesthetics demonstrates that aesthetic experience activates distinct neural networks involving the orbitofrontal cortex for aesthetic judgment, the anterior cingulate cortex for emotional processing, and specialized visual regions for pattern recognition—systems that require sufficient visual complexity to engage properly.

Phrases that become quotes tend to be problematic because they are attributed as the truth, and the larger context within which they existed is forgotten. This decontextualization becomes particularly insidious when Western design philosophies are universalized, erasing centuries of sophisticated aesthetic traditions from Arab, Asian, and African cultures that understood abundance not as excess, but as a reflection of divine generosity and intellectual depth.

Less is more only when more is too much—but who defines “too much,” and by what cultural standards?

The Science of Aesthetic Perception: Neurobiological Foundations of Design

Before examining the cultural implications of minimalism versus maximalism, we must understand the fundamental science underlying human aesthetic perception. Contemporary neuroscience reveals that beauty is not merely a subjective preference but involves sophisticated biological systems that have evolved to process pattern, proportion, and cultural meaning.

The Aesthetic Brain: How We Process Beauty

Neuroimaging studies using fMRI and EEG technology demonstrate that aesthetic experience activates distinct neural networks different from purely cognitive or perceptual processing. Key brain regions involved include the orbitofrontal cortex for aesthetic judgment, the anterior cingulate cortex for emotional processing, specialized visual regions for pattern recognition, and the striatum for reward processing. This reveals aesthetic experience as involving three interacting systems: sensory-motor processing of immediate features, emotion-valuation systems handling pleasure responses, and meaning-knowledge systems integrating cultural context.

Research demonstrates that humans have evolved sophisticated pattern recognition capabilities that respond preferentially to mathematical relationships like the golden ratio, symmetrical forms, and complex geometric arrangements. These preferences are not arbitrary cultural constructions but reflect fundamental aspects of how our visual system constructs understanding of environmental structure.

The Mathematics of Beauty: Universal Principles Across Cultures

The golden ratio (φ ≈ 1.618) appears consistently across cultures and historical periods, from Islamic geometric patterns to classical Greek architecture to contemporary neuroscience laboratories. Brain imaging studies show that viewing compositions incorporating golden ratio proportions activates specific neural reward systems in ways that arbitrary proportions do not. The Fibonacci sequence underlying the golden ratio appears throughout nature—sunflower arrangements, nautilus shells, human body proportions—suggesting biological rather than purely cultural foundations for certain aesthetic preferences.

This mathematical foundation provides objective constraints on aesthetic judgment while leaving substantial room for cultural variation and individual expression. Understanding these universal principles helps explain why certain design approaches satisfy human perception while others feel incomplete or unsatisfying.

The human brain bases a lot of its aesthetic sensibilities on the principle of recognizing a pattern. Our natural disposition is to find a pattern and also insert ourselves in patterns. So, what about Minimalism, does it not have a pattern? Indeed, minimalism has created its own pattern—one of cultural homogenization that flattens the rich diversity of global aesthetic traditions into a monotonous beige uniformity.

Neuroscientific research on pattern recognition reveals why minimalism ultimately fails to satisfy human aesthetic needs. Studies using fMRI brain imaging show that while simple patterns activate basic visual processing areas, complex mathematical patterns like those found in traditional Islamic art activate additional regions associated with problem-solving, meditation, and emotional reward. The brain literally finds more pleasure and engagement in sophisticated patterns than in minimal ones.

Deconstructing “Less Is More”: Cultural Context and Colonial Implications

Minimalism relies on the stripping of the unnecessary to reveal to the viewer the most basic iteration of a specific design. It functioned on the principle of deconstructing something and leaving it as such, sometimes presenting its packaged bare bones without aesthetic elements, and other times, offering a cohesive presentation that strays away from complication. This process of “stripping” and determining what is “unnecessary” inherently carries cultural bias. What Western eyes perceive as superfluous may be essential cultural signifiers in Arab, Persian, or South Asian contexts.

This unintentionally resulted in the uniformity of characteristics, and one can observe this in much of modern architecture and modern interior design. What was perhaps most damaging was not minimalism’s aesthetic choices, but its implicit suggestion that centuries of cultural ornamentation represented primitive excess rather than sophisticated expression.

This cultural violence becomes particularly problematic when we consider the neurobiological evidence: research demonstrates that humans actually thrive in environments providing visual richness, cultural meaning, and sensory engagement. The geometric patterns of Islamic art, for instance, have been shown to reduce stress, promote meditation, and enhance cognitive function—effects that sterile minimalism simply cannot achieve. Studies conducted at the University of Cambridge demonstrate that viewing traditional Islamic geometric patterns activates specific neurological responses associated with meditative states, stress reduction, and cognitive enhancement.

Minimalism has this obsession with flow; it requires this cohesion to function, and any hindrance, if present, needs to then be an anomaly within the design language. Making that object akin to something sacred. This sanctification of the singular object ironically mirrors the Islamic concept of tawhid (unity), yet minimalism achieves this through subtraction while Islamic aesthetics achieves unity through the harmonious multiplication of divine patterns.

Minimalism requires you to cut off everything that was unnecessary, revealing only the bare minimum of whatever it is that’s being designed. An expression so restrained that one needs to spend time dissecting each and every component to find what lies at the core. This archaeological approach to meaning stands in stark contrast to Arab maximalist traditions, where meaning is immediately apparent, generously displayed, and celebrates the viewer’s intelligence rather than testing it.

The Cultural Violence of Aesthetic Imperialism

The universalization of minimalist principles represents a form of aesthetic colonialism that parallels historical patterns of cultural domination. When Western institutions declare that traditional Arab geometric patterns are “too busy,” that Persian carpet designs are “overwhelming,” or that African textile traditions are “chaotic,” they perpetuate the same hierarchical thinking that justified political and economic colonialism.

This aesthetic imperialism has measurable consequences. Research demonstrates that people disconnected from their cultural aesthetic traditions experience higher rates of depression, anxiety, and cultural alienation. Conversely, environments incorporating culturally authentic design elements show improved psychological outcomes, stronger community bonds, and enhanced cultural identity among users.

Understanding Cultural Maximalism vs. Capitalist Hypermaximalism

Maximalism, on the other hand, is closest to human expression, character, and the human tendency to multiply and the greed that exists within it. Yet to characterize maximalism as mere greed reveals a profound misunderstanding of cultures where abundance signifies karam (generosity) and jud (magnanimity)—spiritual virtues rather than material vice.

This mischaracterization reflects the West’s tendency to project capitalist consumption models onto all forms of abundance. Research in environmental psychology reveals that humans have evolved to appreciate visual richness as an indicator of environmental health, social prosperity, and cultural sophistication—responses that predate capitalism by millennia.

One could say that the capitalist society that we live in today operates on the fundamentals of Hypermaximalism. However, there exists a crucial distinction between capitalist hypermaximalism—which accumulates without meaning—and cultural maximalism, which layers significance upon significance in service of community, spirituality, and intellectual discourse.

Cultural maximalism serves specific psychological and social functions that hypermaximalism cannot fulfill. Traditional maximalist environments create what anthropologists call “meaning-rich spaces”—environments where every object, pattern, and color serves multiple functions simultaneously: aesthetic pleasure, cultural education, spiritual contemplation, and social bonding. As documented in Arab maximalist research, traditional Arab homes featured elaborate guest quarters that demonstrated host cultivation and respect for visitors, with abundance serving the community rather than the ego.

Hoarding culture can be attributed to maximalism, as sometimes your aesthetic choices require you to have every colour or every iteration of an object to appease your aesthetic sensibilities. This conflation of maximalism with hoarding represents perhaps the most damaging mischaracterization of sophisticated cultural traditions. True maximalism—as practiced in Arab majlis design, Persian garden planning, or Ottoman palace architecture—operates through careful curation, not mindless accumulation.

Psychological research reveals fundamental differences between cultural maximalism and hoarding behavior. Cultural maximalism involves systematic organization according to traditional principles, serves community functions, and creates positive emotional responses. Hoarding involves random accumulation, serves individual anxiety reduction, and creates negative emotional responses. The distinction is crucial for understanding maximalism as a sophisticated cultural practice.

Rather, at its most sophisticated, maximalism is the physical attribution of our personality, giving shape, colour, and texture to our person. It becomes the visual manifestation of cultural memory, spiritual aspiration, and intellectual achievement—a three-dimensional autobiography written in pattern, color, and form.

Contemporary research in environmental psychology confirms this insight: people living in culturally authentic maximalist environments report higher levels of cultural identity, stronger community connections, better mental health outcomes, and greater life satisfaction compared to those in generic minimalist spaces.

Post-Pandemic Emotional Awakening and Contemporary Maximalism

The roots of maximalism’s contemporary comeback trace directly to our collective psychological response to recent global challenges. As documented in current maximalism research, “with this shift that occurred during the pandemic, we were more inclined to dress for internal factors,”—and this principle has extended far beyond fashion into our living spaces. People are actively seeking joy, individuality, and creative freedom in their environments after years of uncertainty and restriction.

“After years of economic uncertainty and social restrictions, consumers are seeking joy, individuality, and creative freedom in their wardrobes and living spaces.” This psychological shift represents more than aesthetic preference—it reflects fundamental human need for environments that support emotional well-being and cultural expression rather than institutional conformity.

Research consistently shows that maximalist design approaches offer measurable psychological benefits in post-pandemic contexts. Studies indicate that maximalist interior design posts achieve 340% higher engagement than minimalist content, with “dopamine decor” hashtags generating a 280% increase in searches. This suggests a genuine neurochemical response to visual abundance that minimalism cannot provide.

The Question We Must Answer

Given this comprehensive analysis of the neurobiological, cultural, and psychological evidence against pure minimalism, and the equally compelling case against chaotic maximalism, we face a fundamental question: How can contemporary design transcend the false binary of minimalism versus maximalism to create environments that honor cultural authenticity while serving contemporary needs? The answer lies not in choosing sides in this artificial war, but in understanding how sophisticated cultures—particularly Arab aesthetic traditions—have always navigated abundance and restraint through principles that achieve both visual richness and spiritual clarity. The solution demands new frameworks that escape Western design limitations while honoring the mathematical precision, cultural depth, and community wisdom embedded in traditional Arab maximalism.

This is the challenge we must address: developing design approaches that serve human flourishing in all its complex, culturally specific dimensions while creating spaces that are simultaneously rich and ordered, traditionally rooted and contemporarily relevant, individually satisfying and communally beneficial.

Read 2 articles for free

Sign in or create a free account with your email to unlock 2 free articles.